Sharing a Peaceful Moment...Merry Christmas

Thursday, December 20, 2012

Friday, December 7, 2012

Twelve Days of Christmas at Butchart Gardens, Victoria, BC

Now here's one garden that shines during the winter!

Thursday, November 22, 2012

Dr. Andy Davis' Irrigation System for the Triangle Garden

The Powell River Garden Club's Treasurer was pleased to present a cheque for $303.78 to The Townsite Heritage Society. The cheque represented donations made by our members towards Dr. Andy Davis’ fundraising effort to have an irrigation system installed at the Triangle Gardens.

For further reading, please click here.

For further reading, please click here.

What a terrific idea...

...a leaf exchange and community chipping!

Linda Gilkeson's November 22nd Newsletter advised Salt Spring Island gardeners of a free leaf exchange happening on Saturday, November 24th at Rainbow Road Park from 10:00 am to 2:00 pm. As well, participants are welcome to bring tree prunings and branches suitable for chipping ($5 suggested donation for a pickup load to cover the cost of chipping).

Why didn't we think of that!

Linda Gilkeson's November 22nd Newsletter advised Salt Spring Island gardeners of a free leaf exchange happening on Saturday, November 24th at Rainbow Road Park from 10:00 am to 2:00 pm. As well, participants are welcome to bring tree prunings and branches suitable for chipping ($5 suggested donation for a pickup load to cover the cost of chipping).

Why didn't we think of that!

| Fallen leaves scattered around Cenotaph in Powell River's Townsite |

Sunday, November 18, 2012

Do You Have Gardening Obsessive Compulsive Disorder?

Just wanted to share a fun video from Donna, of Donna's Garden on Youtube.

Recognize anyone you know?!

Thursday, November 15, 2012

Winter Lecture Series - Using plants for the ecological restoration of contaminated sites

Presented by: Vancouver Island University, Powell River Campus

Speaker: Dr. Valentin Schaefer, Ph.D., R.P.Bio.

Using plants for the ecological restoration of contaminated sites

Adjacent to our beautiful Powell River Willingdon Beach Park, there is a parcel of land (approximately 10 hectares) previously used as a municipal incinerator site. This land was given to our community for park purposes by the province in 1966; but in 1972 a garbage incinerator was built on the site. This incinerator (pit burner) handled household garbage and commercial waste from the region and, for several years, it also accepted large quantities of paper from the local mill. It operated until the early 90s when the Ministry of Environment ordered it to be shut down due to failure to meet its permit requirements.

Because this site is known to be contaminated with heavy metals, the local Municipality and/or Regional District is obliged to submit a clean-up and remediation plan to the B.C. Ministry of Environment by the end of 2013. A detailed assessment to identify all sources and types of contamination will be part of that plan.

Powell River Botanic Garden Society has recently been formed, and the Society's objective is to have this parcel of land identified as a botanic garden as its future intended use. Most importantly, they see the development of the garden as an opportunity to research how plants may be used to remove contaminants, potentially at considerably less cost than other remediation methods (e.g., transporting the contaminated soils to a secure landfill) while at the same time creating an attractive public space. If successful, Powell River Botanic Garden Society believes this approach would gain the attention of many other public and private interests faced with having to clean up contaminated properties.

Dr. Valentin Schaefer, Ph.D., R.P.Bio., is a biologist and ecologist by training who has developed unique expertise in the emerging field of Urban Ecology. Dr. Schaefer has been the Faculty Coordinator of the Restoration of Natural Systems Program that is offered jointly by the School of Environmental Studies and the Division of Continuing Studies at the University of Victoria, BC, since 2005. He and his graduate students undertake research projects in ecological restoration, the most recent of which is Restoring Urban Nature (RUN). They also provide policy support to the BC Ministry of the Environment and the District of Saanich. Dr. Schaefer is a leading proponent of urban ecology and urban biodiversity who has written extensively and presented internationally on these topics.

The Vancouver Island University together with the Powell River Botanic Society invite all interested parties to attend what promises to be a highly informative and important lecture.

- Date: Mon Nov 19, 2012

- Time: 5:00 PM to 7:00 PM

- Campus/site: Powell River

- Building or Location: Main Campus, 100 - 7085 Nootka Street

- Room: 134

- Cost: $5.00

- Contact: Xochitl Hernandez 604-485-2878 Xochitl.Hernandez@viu.ca

- Contact: Diana Wood 604-2860 (no calls after 9:00 pm) boxwoodcottage@shaw.ca

The Garden Club and Mr. Des Kennedy

The Garden Club and the Kumquat Campaign, a novel by Des Kennedy

"In this warm and humorous novel, narrator Joseph Jones leads us into the world of Upshot Island, an imaginary place off the coast of British Columbia. Joseph's life takes an interesting turn when members of the local garden club decide to take part in the effort to save the Kumquat Sound rain forest. What starts out as a peaceful pilgrimage turns into an outrageous adventure. Along the way, readers will meet the strange characters who inhabit Upshot Island, such as Elvira Stone who believes her missing husband was abducted by a UFO and Waddy Watts, a cantankerous old-timer who predicts the next rainfall by the sound of the frogs. Award-winning garden writer Des Kennedy's descriptions of coastal plants create a perfect natural environment for the story. His intriguing narrative delves into realms of mystery, death, and love.

...The Garden Club is a must-have for all lovers of the outdoors."**

**Book description found at 49th Shelf.

A copy of The Garden Club, short-listed for the Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour, is available for loan from our wonderful Powell River Public Library.

Other Des Kennedy titles available for loan from the library are:

"In this warm and humorous novel, narrator Joseph Jones leads us into the world of Upshot Island, an imaginary place off the coast of British Columbia. Joseph's life takes an interesting turn when members of the local garden club decide to take part in the effort to save the Kumquat Sound rain forest. What starts out as a peaceful pilgrimage turns into an outrageous adventure. Along the way, readers will meet the strange characters who inhabit Upshot Island, such as Elvira Stone who believes her missing husband was abducted by a UFO and Waddy Watts, a cantankerous old-timer who predicts the next rainfall by the sound of the frogs. Award-winning garden writer Des Kennedy's descriptions of coastal plants create a perfect natural environment for the story. His intriguing narrative delves into realms of mystery, death, and love.

...The Garden Club is a must-have for all lovers of the outdoors."**

**Book description found at 49th Shelf.

A copy of The Garden Club, short-listed for the Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour, is available for loan from our wonderful Powell River Public Library.

Other Des Kennedy titles available for loan from the library are:

- The Way of a Gardener: A Life's Journey

- Climbing Patrick's Mountain

- An Ecology of Enchantment: A Year in the Life of a Garden

- Living Things We Love to Hate

- The Passionate Gardener

|

| Des Kennedy |

Wednesday, November 14, 2012

Jabuticaba...Fascinating Tree, Wouldn't You Agree?

|

| Jabuticaba Tree Native to South America |

- The Jabuticaba Tree, otherwise known as the Brazilian Grape Tree, is native to South America, notably Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil

- The purple fruit can be plucked and eaten straight from the tree

- The Jabuticaba tree prefers moist and slightly acid soils but will even grow well in alkaline soil

- The flowers, found along the trunk and branches appear on the tree twice a year. The habit of flowers doing this makes them cauliflorous. Instead of growing new shoots, these plants flower direct from the woody trunk or stem.

- The tree has evolved in this manner so that animals that cannot climb very high can reach it, eat it and then expel the seeds away from the parent tree to further propagate the species.

- If the tree is well irrigated it will flower and fruit all the year round. The fruit itself is about four centimeters in diameter and has up to four large seeds.

- As well as being used as food, the skins can be dried out and used to treat asthma and diarrhea.

- If your tonsils are swollen you can also use it to alleviate the inflammation. It is also hoped that the tree will be useful in the fight against cancer, as several anti-cancer compounds have been found in the fruit

- It is a popular ingredient in jellies, can be juiced to make a refreshing summer drink, and it can be fermented and made into wine and strong liquor. It is interesting to note that after three days off the tree, fermentation begins

|

| Jabuticaba Tree in flower |

|

| Ripe fruit on Jabuticaba Tree Article shared by PRGC member, Lexie |

Permaculture Powell River Information Night

What's all the buzz about permaculture in Powell River these days? Join us for a lively information session introducing you to the powerful possibilities of permaculture for our region. Find out more about the second year of our community-based permaculture design certificate program (PDC) starting in January 2013 and the public permaculture garden now underway in Townsite. Film, music, conversation and just plain fun!

Wednesday, November 21 7:30 -8:30 pm

Townsite Anglican Church, 6310 Sycamore Street

Admission by donation (all proceeds go to our program scholarship fund)

For more information:

contact Erin Innes (604-483-4050 erininnes@gmail.com)

or Ron Berezan (604-223-4800 theurbanfarmer@shaw.ca)

or visit www.permaculturepowellriver.ca

Hope to see you there!

Submitted by Ron Berezan and Erin Innes

Wednesday, November 21 7:30 -8:30 pm

Townsite Anglican Church, 6310 Sycamore Street

Admission by donation (all proceeds go to our program scholarship fund)

For more information:

contact Erin Innes (604-483-4050 erininnes@gmail.com)

or Ron Berezan (604-223-4800 theurbanfarmer@shaw.ca)

or visit www.permaculturepowellriver.ca

Hope to see you there!

Submitted by Ron Berezan and Erin Innes

Monday, November 12, 2012

Friday, November 9, 2012

News from The Bulletin November/December 2012

As members of the BC Council of Garden Clubs (BCCGC) the Powell River Garden Club receives The Bulletin bi-monthly throughout the year. The Bulletin contains news and information from the Council as well as informative and interesting articles submitted by Club members.

Below, please find many of the articles published in The Bulletin, November/December 2012. A printed copy of The Bulletin is available at Club meetings.

Article #1 The Summer That Almost Wasn't...Keith Harris

Article #2 Fraser Valley Orchid Show Report...Janice Jenkins

Article #3 Lithops aka Living Stones...

Article #4 Dr. Willard's Catalyst Altered Water...Chris Crapper

Article #5 Invasive Plant Species - Giant Hogweed

Article #6 Which is the Best Mulch for You? by Phil Nauta

Article #7 Mealybugs...Various Sites

Article #8 Itoh Peonies...Various Magazines and Sites

Article #9 The Dirty Dozen...Pesticide Residue in Food

Article #1 The Summer That Almost Wasn't...Keith Harris

I'm certain that we’re all familiar with the headlines relating to "Global Warming." Yet, when referenced to our weather during the early months of this year, one can only wonder what meaning one gets from that statement ... Global Warming, indeed!

At the start of this year, tending to my garden began as it had during each of my 45 plus years of working my garden in Burnaby. In mid-January I emptied my compost bin, to spread the 4 cubic yards of nature's black gold, generated during the previous season, across the 1,000 square feet of my vegetable bed, to allow natural forces to work the nutrients into the soil. In early March I laid out my 8-foot long cedar planks onto the soil in a grid pattern, to establish the paths on which I walk among my vegetables during the season. I use a basic increment of 4-ft by 8-ft for most of my beds, with multiples of this dimension for vegetables requiring additional space.

In late March I pull the soil up away from the plank-paths, to form a ‘raised bed’ between the wooded paths between them. This allows the soil to warm up quickly and to drain easily. In March I also visit my local garden store to buy the vegetable seeds that I plan to plant for the year.

During past years, I’ve put my vegetable seeds into the ground in late April / early May, as the occasion presents itself. I followed this practice again this year. Who can forget our experience this year, a decidedly wetter and cooler than normal April and May. During the next ‘couple of weeks’, with nothing showing above the ground I reseeded my vegetables in mid-May, and again in June. It was a truly frustrating experience.

Starting in May of each year, the professional gardener who services our neighbourhood gardens begins delivering to my garden the grass clippings from local properties, along with pruned plant material, as fodder for my compost bins. In anticipation of the hot sun that is a ‘normal’ expectation in June, I began to mulch my beds with the fresh grass clippings, although my seedlings were not yet all showing their heads above ground.

My perseverance paid off in July, when the sun finally arrived. In the short space of about 10 days we had moved from winter through spring and into the heat of summer. The mulch I placed between the rows of vegetables paid off. I found I needed to water my vegetables no more than at ten-day intervals.

My harvest for this season has been poor, certainly less yield than harvested in regular years, and nowhere near the harvest of a vintage year. However, my regular winter crop vegetables, the beets, leeks, parsnips, kohlrabi and Swiss chard have all flourished in the long hours of sunlight we’ve enjoyed since July, and I expect to continue to have a good yield through the winter months.

The BC Weather reports state that late July through to September have been the driest months since weather records were first compiled in the late 1800’s. On review, perhaps there is some truth to ‘Global Warming.’ Next year will be better …?

Article #2 Fraser Valley Orchid Show Report...Janice Jenkins

Fraser Valley Orchid Society’s Annual Show and Sale were held on October 20 and 21, 2012 at the George Preston Recreation Centre. This was their third annual orchid floral arts presentation. The theme this year was: "At Home With Orchids".

The classes were:

Family Buffet - Design suitable for the buffet table

Rhapsody in Blue - Design suitable for the dinner table

Engagement Party - Abstract design suitable for the table

Romantic Dinner - Design of your choice

The published information on the impact of CAW on plant health, growth and yield is available in the following sources:

The purpose for the show theme was to present to the public a number of ways orchids can be used in the home. In addition to having lovely orchid plants to grace their homes, the floral art section was created to encourage the public to use orchid flowers in floral designs.

On Saturday afternoon Radina Jevdevic, who also organized the floral arts section of the show, gave a demonstration on how to design a centerpiece and also a corsage.

The show preview, plant sale and dinner were held on Friday evening for members and exhibitors.

We wish to thank the presiding floral art judge, Marilyn O’Neill, who encouragingly gave many constructive tips to exhibitors on how to improve their designs.

Cindy Tataryn was the winner of Best in Show award for her arrangement in the "Engagement Party" class.

See you at the 2013 Fraser Valley Orchid Society Show.

Article #3 Lithops aka Living Stones...

Lithops aka Living Stones are succulent plants from the ice plant family, Aizoaceae. These are native to the hot, dry areas of southern Africa. Nearly a thousand individual populations are documented, each covering just a small area of dry grassland, veld, or bare rocky ground. Different Lithops species are preferentially found in particular environments, usually restricted to a particular type of rock. Lithops have not naturalized outside this region.

Individual lithops plants consist of one or more pairs of bulbous, almost fused leaves opposite to each other. The slit between the leaves contains the meristem and produces flowers and new leaves. During winter a new leaf pair grows inside the existing fused leaf pair. In spring the old leaf pair parts to reveal the new leaves, then the old leaves will dry up. Lithops leaves may shrink and disappear below ground level during drought. In habitat they almost never have more than one leaf pair per head as the environment is just too arid to support this.

In their third year of growth, yellow or white flowers emerge from the fissure between the leaves after the new leaf pair has fully matured. This is usually in autumn but in some varieties such as L. pseudotruncatella can be before the summer equinox and in L. optica after the winter equinox. Two different plants are required for pollination and seeds take approximately 9 months to mature. Seeds are easy to germinate but the seedlings are small and vulnerable for the first few years.

Lithops are one of the greatest of the camouflage plants as the leaves are not green but are various shades of cream, grey and brown, patterned with darker windowed areas, dots and red lines. This helps to disguise the plant in their surroundings keeping it safe from animals and insects looking for a food or water source.

Lithops require pollination from a separate plant. Lithops fruit is a dry capsule that opens when it becomes wet; some seeds may be ejected by falling raindrops and the capsule recloses when it dries out.

Rainfall in habitats ranges from approximately 700mm per year to nearly zero. Temperatures are usually hot in summer and cool to cold in winter, but one species is found right at the coast with very moderate temperatures year round.

In recent years Lithops have become popular as houseplants and many specialize succulent growers maintain collections. Seeds are widely available in stores and over the web. They are easy to grow if given sufficient sun and a suitable well drained soil.

Normal treatment in temperate climates is to keep them completely dry during winter, watering only when the old leaves have dried up. Watering should continue through autumn when the flowers emerge and then stopped for winter.

Treatment for hotter climates includes summer dormancy when they should be kept mostly dry and given some water in winter. In tropical climates, Lithops can be grown primarily in winter with a long, summer dormancy. In all conditions, Lithops will be most active and need most water during autumn and each species will flower at approximately the same time.

Lithops thrive best in a coarse, well-drained substrate. Any soil that retains too much water will cause the plants to burst their skins as they over-expand. Plants grown in strong light will develop hard strongly coloured skins which are resistant to damage and rot, although persistent overwatering will still be fatal. Excessive heat will kill potted plants as they cannot cool themselves by transpiration.History:

The first scientific description of a Lithops was made by William John Burchell, explorer of South Africa, botanist and artist, although he called it Mesembryanthemum turbiniforme. In 1811 he accidentally found a specimen when he picked up a curiously shaped pebble.

In the 1950s, Desmond and Naureen Cole began to study Lithops. They eventually visited nearly all habitat populations and collected samples from approximately 400, identifying them with the Cole numbers which have been used ever since and distributing Cole numbered seed around the world. They studied and revised the genus, in 1988 publishing a definitive book (Lithops: Flowering Stones) describing the species, subspecies, and varieties which have been accepted ever since.

New species continue to be discovered steadily in remote regions of Namibia and South Africa, most recently L. coleo-rum in 1994, L. hermetica in 2000, and L. amicorum in 2006.

Article #4 Dr. Willard’s Catalyst Altered Water … Chris Crapper

Even if you're an avid gardener there is a very good chance you've never used or even heard of Catalyst Altered Water (CAW), even though its been used to support plant health, growth and yield since about 1975.

What is it?

Catalyst Altered Water is a non-carbonated mineral water containing small amounts of sodium meta silicate, calcium chloride, magnesium sulfate, sulfated castor oil and powdered lignite. It has a pH of 12.34 and is approximately 99.99% organic. The addition of a trace amount (approximately .001%) of sodium meta silicate has prevented full organic certification in the US where CAW was invented and it formulated. CAW attracted public interest in 1980 when the CBS program '60 Minutes' broadcast interviews with people using it in a variety of applications (e.g., drinking; spraying on burns; agriculture, etc; see http://vimeo.com/6596672) . Two agricultural applications in that broadcast (squash and wheat crops) suggested CAW could improve plant growth and yield even in stressful growing conditions (e.g., drought).

How does CAW work?

Dr. John Willard, PhD, inventor of Catalyst Altered Water, claimed his product contains a colloidal particle called a micelle. He suggested the micelle’s strong negative charge attracts water molecules and rearranges their structure. Dr. Willard claimed this rearranged structure makes ‘ordinary’ water (tap water; well water; purified water) more reactive and thus more effective as a water and nutrient transport medium in plants.

How and when to use CAW

You’ve heard the expression ‘just add water’. That pretty much sums up how to use CAW. Just add 60ml (approximately 2 ounces) of CAW to your watering can or reservoir if you are lucky enough to have a greenhouse or a hydroponic garden. You can safely mix CAW with purified water, tap water, well water, distilled water, etc. It is fairly well known in the nutrition industry as a drinking water additive so don’t worry about hurting your favourite plants. It is non-toxic.

You can use CAW any time you water your plants and at any stage in plant growth. You can also use it to support seed germination as it attracts moisture. CAW is an alkaline water (pH = 12.34) that has been shown to raise the pH of any water it is mixed with by up to 2 points. That enhanced alkalinity has potential benefits as a foliar spray. Just add 60mL of CAW to one gallon of any type of water and apply that mixture as part of your normal seed germination or foliar spray routine.

How does it affect plant health, growth and yield?

Catalyst Altered Water is certainly not a magical elixir and research clearly shows that it does not always enhance plant health, growth or yield in every application. The fact this product has been around since the mid seventies however suggests it has some popularity and benefits, as people suggested in the '60 Minutes' program.

Perhaps the most interesting experiments on CAW have been conducted in commercial greenhouses in Canada and the US where both test and control groups of plants have been used. That testing has involved over 100,000 plants including clematis, impatiens, micro and potted spathiphyllum, hydrangea, weigela florida and spiraea japonica. These tests found the following benefits:

Larger and/or greener plants

More blooms or plants blooming earlier

Sturdier stocks or more extensive root systems

Greater resilience in stressful growing environments (eg., drought). More yield per plant, larger fruit/flowers and enhanced flavour and aroma

The published information of the impact of CAW on plant health, growth and yeild is available in the following sources:

Acqua Vitae, Roy Jacobsen, 1992

Catalyst Altered Water, Beth Ley, 1990

"Dr Willard’s Catalyst Altered Water", article by C G Crapper, Maximum Yield, May/June 1999

Editor’s Note: Text in green was revised by the author, October 24, 2012, based on manufacturer’s info re actual organic content.

Article #5 Invasive Plant Species - Giant Hogweed

Giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum), also known as "Giant Cow Parsnip," is a perennial and currently distributed in the Lower Mainland, Fraser Valley, Gulf Islands, and central to southern Vancouver Island.

Giant hogweed has numerous small white flowers clusters in an umbrella-shaped head, with stout, hollow green stems covered in purple spots. Dark green leaves are coarsely toothed in 3 large segments with stiff underside hairs, and lower leaves can exceed 2.5 metres in length. Giant hogweed can grow up to 5 metres in height at maturity.

Giant hogweed is a highly competitive plant due to vigorous early-season growth, tolerance of full shade and seasonal flooding, as well as its ability to coexist with other aggressive invasive plant species. Each plant can produce up to 100,000 winged seeds (typically 50,000) that remain viable in the soil for up to 15 years. Plants generally die after flowering.

Warning: Giant hogweed stem hairs and leaves contain a clear, highly toxic sap that, when in contact with the skin, can cause burns, blisters and scarring. WorkSafe BC has issued a Toxic Plant Warning for Giant hogweed that requires work-ers to wear heavy, water-resistant gloves and water-resistant coveralls that completely covers skin while handling the plants. Eye protection is also recommended.

The Invasive Species Council of British Columbia is a registered charity working collaboratively to build cooperation and coordination of invasive species management in BC. Workshops, activities, and events educate the public and professionals about invasive species and their potential risks.

The ISCBC has grown rapidly since its inception in 2004, and is recognized across the country for its leadership in building collaboration on the challenging and growing problem of invasive species.

To report an invasive plant, or for more information, contact the Invasive Species Council of BC (ISCBC) at www.bcinvasives.ca.

Article #6 Which is the Best Mulch for You? …by Phil Nauta

There are many mulch types available for your organic garden, but which is the best mulch for you? This article explores some of the most popular types of mulch and ultimately comes to a conclusion with what you should use. What is mulch? It's really anything that we put on the soil surface to cover the ground.

Landscaping Fabric - Not the Best Mulch

Landscaping fabric is considered part of our mulch because it is often placed on the soil under various types of mulch in order to help control weeds. The cheap stuff doesn’t work very well, but thicker fabric can work for awhile before weeds start to find their way through the cracks or just start on top of the mulch.

Unfortunately, that thick landscaping fabric can also stop water from getting down to the soil, especially on a slope where the water just slides down the fabric to the bottom. It doesn’t take long for the landscape to show signs of suffering in this case.

But the biggest problem with this fabric is that it doesn’t allow organic matter to recycle into the soil. When you put landscaping fabric on, it means your soil doesn’t get to eat anymore. This is definitely not the best mulch for organic gardening purposes. Soil needs to be consistently replenished with organic matter, so any of the mulch types we choose have to be composed of organic matter.

Soil is replenished in nature and in our gardens when leaves fall in autumn, and since many of our gardens are low in organic matter anyway, it also happens when we intentionally bring in more leaves, straw, compost and other organic matter to improve the soil.

Putting landscaping fabric in the garden stops all of this and slowly kills the fertility and structure of the soil, and everything living in it. The only potential use is on pathways, since we are compacting them anyway and not trying to increase the organic matter. But we need to look elsewhere for the best mulch.

Why Organic Matter is One of the Better Types of Mulch

When it comes to choosing a good mulch, we need to think, what is mulch for?

Weeds

A continuous thick, dense layer of 2" to 4" of one of the best mulch types is one of my favourite ways to control weeds because not only does it smother most of them out, it makes the ones that do find their way through so much easier to pull, especially if you have been clever enough to regularly hit the garden (and the mulch) with some water.

Weed seeds will always be floating in, but a thick mulch will stop them.

We have other organic gardening chores to do, so eliminating most of the weeds is a good goal. It may be necessary to kill some taprooted or perennial weeds before placing the mulch on top of them. In addition, maintaining a dense, multi-layer plant cover on your soil consisting of a groundcover below and flowers, shrubs and trees above will stop most weeds from growing.

But the reason organic matter is the best mulch is that it pro-vides a huge number of benefits to your garden. In fact, it is one of the most important things you can do. If you use an appropriate kind of mulch (we'll get to what is "appropriate" soon), here are the other main benefits:

Soil Health

The best mulch types are persistently and continuously working to improve the health of the soil. They are being broken down by microbes and increasing the organic matter content of the soil.

Organic matter is an incredibly important part of the soil. It improves soil structure, and as it is broken down, its nutrients are releasing into the soil, making it one of the only types of mulch that improves fertility. It prevents compaction from us walking in the garden and erosion from the wind or gravity on steep slopes. It also moderates the soil temperature, which is good for anything (plant, animal and microbe) living there.

Water

Organic matter is the best mulch because it is broken down into humus, which has an incredible ability to hold onto lots of water. But even before it is broken down, mulch holds a lot of water on its own and allows it to more slowly infiltrate into the soil.

It also reduces compaction (and leaching of nutrients) caused by a heavy rain, and erosion that happens when a lot of rain falls and there is runoff. Conversely, when the sun is shining, it also prevents evaporation from the soil surface.

So the best mulch actually improves the biodiversity of your entire soil ecosystem by giving all manner of critters a place to live, food to eat and water to drink. It even looks good in the organic garden if one of the right types of mulch is used.

So what is the best mulch? Well, it has to satisfy all of the conditions in the above article, so we can probably figure it out by a process of elimination. Let's start with mulches that satisfy very few of our conditions and get rid of them right away:

1. Stones or gravel provide some of the benefits in that they protect the soil from erosion and decrease evaporation, but they do not breakdown and so do not do much to improve soil health. They are not one of the best mulch types.

2. Bark mulch and wood chips are no good even though they are some of the most commonly used mulching materials in the garden. You may have seen them in bags or in bulk at the garden center, or you may have used them in your organic gardening before. They do most of the above things well, but unfortunately, they have a couple of big problems making it one of the types of mulch I never use. Bark mulch and wood chips are not the best mulch types. The first is that they are very high in carbon and very low in nitrogen. This means that the beneficial microbes can pull all of the available nitrogen from the surrounding area, which often ends up causing a nitrogen deficiency in your plants.

And bark in particular is very low in nutrients (so it doesn't improve soil fertility) and often high in toxins (it’s a tree’s first line of defence against pests), so it causes toxicity problems in the soil. It even contains oils that repel water, rather than more appropriate mulch materials that will hold onto water.

3. Straw and Hay are not the most aesthetically pleasing, but they are fairly good types of mulch. They are used in organic gardening, but the main issue for most people will be that it is not always easy to find and it breaks down so quickly that it has to be applied multiple times a year.

You may not want to use straw or hay from ryegrass as it has toxins in it, and definitely not from grass that has been sprayed with pesticides such as Roundup, which is common in many countries. The difference between straw and hay is that hay has seeds, so it will often actually produce weeds.

4. Grass clippings are not the best mulch to use in organic gardening because they get so tightly packed together that they inhibit air circulation. Besides, they are far too important for the soil of your lawn to bring into the garden. They do not contribute to thatch or any other lawn problems, but they pro-vide many benefits so they must be left there.

5. We're getting closer to my favourite of all mulch types, but not yet. With all this talk about organic matter, why not just use compost? A little bit of thought tells us why. It does a lot of things right, but fails to stop the weeds! The same goes with manure, and manure needs to be composted before applied to soil anyway. We should use compost and manure, but they are not really the best mulch. I cover compost in detail in the Smiling Gardener Academy along with cover crops because they are both excellent ways to increase the organic matter content of the soil, but here, we're looking for the best mulch.

The Best Mulch Types

What is mulch, I mean the best mulch - what is it? It's organic matter and it's provided by nature. In a well-designed organic garden, this is one of the only types of mulch that magically appears in our beds in autumn, protecting the soil over winter, and breaking down throughout the following spring and summer until a new batch magically appears in autumn.

Number 1

Of all the mulch types, by far the best for organic gardening is: leaves! They do absolutely everything right. That's why when we're designing our gardens we want to make sure to use plants that make a lot of leaves - not just evergreens - and we want to design the beds to catch all of these leaves.

Leaves are by far the best mulch type

Those that fall on the lawn and non-garden surfaces can be raked into the gardens or mulched right on the lawn.

If you don't have enough leaves, your neighbours will usually be happy to give you theirs, since they would otherwise have to rake them up and dispose of them. In many cities, you can rake your leaves to the curb and a big truck will come by to pick them up. But why would you want to give the best mulch ever away unless you have too many?

Ironically, some organic gardeners do this and then buy the leaves back as leaf mould in the spring. Leaf mould is just leaves that have been slightly decomposed. Leaf mould is one of the best mulch types, too, but in most cases, the gardener would have done much better to save the money and keep the leaves in the garden over winter where they can protect the soil.

If you have a thick enough layer of leaves in your garden (2" to 4" is nice), many weeds will be smothered. You will still get some weeds, but they will be so easy to pull that it won't matter. You can just drop them back on top of the leaves to become part of the best mulch ever.

Some people think leaves are not one of the most attractive types of mulch for the garden, but is a forest floor unattractive? Or is the forest floor covered in 2 inches of bark? We’ve been conditioned to think that bark mulch or bare soil is the most aesthetically pleasing, but if you covered your organic garden in a rainbow of autumn leaves, I think you’ll see it differently, especially now that you know all the benefits they provide. When we remove the leaves, we are breaking nature's cycle and creating more work for ourselves.

So leaves are the number one best mulch.

Number 2

There is one other organic gardening material that doesn't take the place of leaves as the ultimate of all the types of mulch, but it is beneficial to have as well. It's called a living mulch, i.e. plants. A living mulch is a dense plant cover on the soil, especially low growing "cover" crops.

These can be annual crops (also known as green manures) that we plant in our vegetable gardens to protect the soil during certain times of year and to provide organic matter to the soil, or perennial plants (also known as groundcovers) that live permanently in our ornamental gardens underneath our flowers, shrubs and trees.

A good goal is to make sure all of your soil is consistently covered with plants, and cover crops help achieve this goal. Plants send out hormones in the vicinity of their roots that tell weed seeds not to grow.

As long as your organic garden is dense with plants and leaves (the best mulch ever), and your lawn is dense with healthy grass, those weed seeds will mostly stay dormant and you have a whole list of other benefits to which you can look forward.

Mulching All Your Leaves - There Are Exceptions

It is possible to have too many leaves if you have a lot of big trees or if your beds are already covered in groundcovers and you don't want to totally smother them. In that case, you may just have to compost them or give some away, to a friend or to the city, although I have mulched 12 inches of leaves into some lawns with great success.

Actually, when I was a kid, I recall my dad would pile a bunch of leaves in the back of the pickup truck (we lived in the country), head down the street to where there were no houses, drop the tailgate, and hit the gas. It was so much fun watching the leaves get caught by the wind and cover the sky like a thousand red and yellow butterflies. In hindsight, I have no idea why we did this, but it was fun at the time.

I know someone reading this is wondering about oak leaves. I've never had a problem with the fact that oak leaves don't break down quickly. I've always enjoyed that about them because it just means my mulch stays around longer. And nope, they don't acidify the soil. But again, if you have too many, don't force it.

Editor’s Note: Phil Nauta is an organic gardener on the East Coast. His website is extremely informative. Should you wish to avail yourself of this incredible resource, here is the link.

http://www.smilinggardener.com

Article #7 Mealybugs...Various Sites

Mealybugs are soft bodied insects in the family Pseudococcidae, They have a white powdery substance over their bodies and white, waxy filaments projecting from the rear of their bodies. They are unarmored but have a rubbery outer coating that cannot be detached. They are considered pests as they feed on plant juices of greenhouse plants, house plants and subtropical trees and also acts as a vector for several plant diseases.

Mealybugs sexes have distinct morphological differences. Females are nymphal, exhibit reduced morphology, and are wingless, though unlike many female scale insects, they often retain legs and can move. The females do not change completely and are likely to exhibit nymphal characteristics. Males are winged and do change completely during their lives. Since mealybugs are hemimetabolous insects, they do not undergo complete metamorphosis in the true sense of the word, i.e. there are no clear larval, pupal and adult stages, and the wings do not develop internally. However, male mealybugs do exhibit a radical change during their life cycle, changing from wingless, ovoid nymphs to "wasp-like" flying adults.

Mealybug females feed on plant sap, normally in roots or other crevices. They attach themselves to the plant and secrete a powdery wax layer used for protec-tion while they suck the plant juices. The males on the other hand, are short-lived as they do not feed at all as adults and only live to fertilize the females.

Most species lay batches of eggs in masses of waxy strands, called ovisacs. However, there are some mealybug females that are ovoviviparous (giving live birth to first instar nymphs) and/or parthenogenic. The first instar nymphs are often called crawlers, but the second instar nymphs are also motile. In bisexual species of mealybugs, male nymphs undergo an extra instar that is called the "pupa" which has external wing pads and is a non-feeding sessile stage. These pupae give rise to winged males, but these males are unique in that they only have one pair of wings. The hind pair of wings have been lost. If the mealybug is a female, the second instar simply molts into another nymph-like form but this stage is sexually mature.

The long-tailed mealybug is slightly different in that females give birth to living young. The complete life cycle can take six weeks to two months depending on the species and the environmental conditions. Breeding and development, however, is year-round in the greenhouse.

The most serious pests are mealybugs that feed on citrus. Mealybugs also infest some species of carnivorous plant such as Sarracenia (pitcher plants), in such cases it is difficult to eradicate them without repeated applications of insecticide such as diazinon. Small infestations may not inflict significant damage. In larger amounts though, they can induce leaf drop. Mealybugs can be controlled using the biocontrol agent Verticillium lecanii.

Article #8 Itoh Peonies...Various Magazines and Sites

'Itoh' peonies have a long and remarkable story. Dr. Toichi Itoh, an extremely determined and dedicated man, spent twenty years trying to accomplish what others said couldn’t be done, he managed to make an intersectional cross between tree peonies (Moutan) and herbaceous peonies (Paeon). He started in the early 1900’s and made 20,000 crossings before he finally succeeded in 1948. The first ever cross between P. x lemoinei (a hybrid yellow tree peony) with P. lacti-flora ‘Kakoden’, a white flowered herbaceous peony which was used as the seed parent. He had 36 seedlings with this successful cross, some of which had the dominant characteristics of the tree peony and these became the first ‘inter-sectional’ hybrids.

In 1964 Dr. Itoh’s first crosses came into bloom but unfortunately Dr. Itoh passed away in 1956, eight years before the first blooms appeared and he never saw the results of his successful crosses. Of the thirty-six, six were considered outstanding and these became the first herbaceous peonies to have deep yellow, double flowers.

Early propagation of these peonies were unsuccessful because plants were repeatedly lost to fungal pathogens. However in the late 1960’s an American horticulturist, Louis Smir-now, purchased four selections from Dr. Itoh’s widow and imported them into the United States. He patented these hybrids as: ‘Yellow Emperor’, ‘Yellow Crown’, ‘Yellow Heaven’ and Yellow Dream’. These first hybrids were inferior, from a horticultural point of view, to the Itohs now available, but these first crosses inspired a number of American breeders to attempt similar crosses, in particular Roger Anderson, Don Hollingsworth and Don Smith.

The first introductions were sold for between $200 to $1,000 each which only allowed wealthy collectors to pur-chase them. Anderson is now the best-known breeder of intersectional peonies. He has raised about 400 cultivars, including ‘Cora Louise’, ‘Copper Kettle’ and in 1986 ‘Bartzella’. Divisions of ‘Bartzella’, a highly desirable cultivar, were sold for $1,000 U.S. each. One of his latest hybrids, ‘Sequestered Sunshine’, is selling well as a florist's flower. Don Hollingsworth, of Missouri, produced ‘Garden Treasure’.

In the 1970s, the American Peony Soci-ety looked at the new hybrids and named them after Itoh. Many breeders still prefer to call them "intersectional hybrids."

High prices and lack of availability have made these varieties particularly attractive for micropropagation.

Enter Planteck a Canadian based company. In 2004, Planteck hit on a new technique using tissue culture in a laboratory to achieve a high rate of success. Planteck is now the only company in the world that can produce Itoh peonies in mass numbers.

Growth Habits:

Peonies have a determinant herbaceous growth habit, mea-ning that next season’s growth is determined by bud and storage root development in the fall. On herbaceous peonies, buds are located at the crown of the plant and protected by the soil. On tree peonies, the buds are located on lignified branches above soil and often not protected by snow, there-fore they are not as winter har-dy as herbaceous peonies. Itohs have an intermediate growth habit with most buds at the crown, but often some on the lower part of the stem as well.

This determinant growth habit makes peonies recalcitrant to in vitro propagation. Despite this, Planteck has developed an economically feasible method for the micropropagation of peonies. Planteck’s micropropagation program has been successful with all three major groups of peonies: herbaceous, tree and Itohs. Genotype still has an important role to play and some cultivars from each of these groups respond better than others.

The tree peonies generally multiply very well, but rooting is more difficult. This is only natural given that tree peonies are usually grafted onto herbaceous nurse-roots until their own roots are strong enough to take over. The advantage of micropropagated tree peonies is that they are immediately growing on their own roots.

Advantageous features of Itoh peonies:

There are reputable groups that issue annual lists with regards to the fruits and vegetables we purchase and their chemical residue content.

Please note that all fruit and vegetables were prepared, as though you were planning to eat them. That means if you peel a banana or wash an apple before eating, so do they before testing.

Here are the culprits called ‘The Dirty Dozen’ by the EWG (Environmental Working Group) with the No.1 spot having the most residue and the No.12 spot the least.

At #1 Apples: 98% of 700 different samples showed pesticide residue. 40 different pesticides were noted. (#3 last year).

#2 Celery: was No.1 last year. 57 different pesticides were noted. Purchase organic celery or grow your own.

#3 Sweet Bell Peppers -15 different pesticides on a single sample.

#4 Peaches - 60 pesticides in fresh fruit but a little fewer in canned peaches.

#5 Strawberries - 54 residues were found on strawberries. 14 different pesticide residues were detected in one strawberry sample. 697 of 741 strawberries tested positive for residues.

#6 Nectarines, imported - 33 pesticides on nectarines.

#7 Grapes - 30 pesticides found on grapes with raisins testing the same. Not mentioned was wine.

#8 Spinach - 50 pesticides whether in fresh of frozen. Canned spinach has a little less.

#9 Lettuce - more than 50 pesticides have been identified on lettuce. Grow your own is the best advice.

#10 Cucumbers - 40 pesticides found on cucumbers.

#11 Blueberries, domestic - more than 50 pesticides found on blueberries. Frozen blueberries have proven to be somewhat less contaminated. 14 of the 50 pesticides residues found on blueberries are neurotoxins, which can harm brain development and contribute to falling IQs.

#12 Potatoes - 35 pesticides found on potatoes.

Below, please find many of the articles published in The Bulletin, November/December 2012. A printed copy of The Bulletin is available at Club meetings.

Article #1 The Summer That Almost Wasn't...Keith Harris

Article #2 Fraser Valley Orchid Show Report...Janice Jenkins

Article #3 Lithops aka Living Stones...

Article #4 Dr. Willard's Catalyst Altered Water...Chris Crapper

Article #5 Invasive Plant Species - Giant Hogweed

Article #6 Which is the Best Mulch for You? by Phil Nauta

Article #7 Mealybugs...Various Sites

Article #8 Itoh Peonies...Various Magazines and Sites

Article #9 The Dirty Dozen...Pesticide Residue in Food

Article #1 The Summer That Almost Wasn't...Keith Harris

I'm certain that we’re all familiar with the headlines relating to "Global Warming." Yet, when referenced to our weather during the early months of this year, one can only wonder what meaning one gets from that statement ... Global Warming, indeed!

At the start of this year, tending to my garden began as it had during each of my 45 plus years of working my garden in Burnaby. In mid-January I emptied my compost bin, to spread the 4 cubic yards of nature's black gold, generated during the previous season, across the 1,000 square feet of my vegetable bed, to allow natural forces to work the nutrients into the soil. In early March I laid out my 8-foot long cedar planks onto the soil in a grid pattern, to establish the paths on which I walk among my vegetables during the season. I use a basic increment of 4-ft by 8-ft for most of my beds, with multiples of this dimension for vegetables requiring additional space.

In late March I pull the soil up away from the plank-paths, to form a ‘raised bed’ between the wooded paths between them. This allows the soil to warm up quickly and to drain easily. In March I also visit my local garden store to buy the vegetable seeds that I plan to plant for the year.

During past years, I’ve put my vegetable seeds into the ground in late April / early May, as the occasion presents itself. I followed this practice again this year. Who can forget our experience this year, a decidedly wetter and cooler than normal April and May. During the next ‘couple of weeks’, with nothing showing above the ground I reseeded my vegetables in mid-May, and again in June. It was a truly frustrating experience.

Starting in May of each year, the professional gardener who services our neighbourhood gardens begins delivering to my garden the grass clippings from local properties, along with pruned plant material, as fodder for my compost bins. In anticipation of the hot sun that is a ‘normal’ expectation in June, I began to mulch my beds with the fresh grass clippings, although my seedlings were not yet all showing their heads above ground.

My perseverance paid off in July, when the sun finally arrived. In the short space of about 10 days we had moved from winter through spring and into the heat of summer. The mulch I placed between the rows of vegetables paid off. I found I needed to water my vegetables no more than at ten-day intervals.

My harvest for this season has been poor, certainly less yield than harvested in regular years, and nowhere near the harvest of a vintage year. However, my regular winter crop vegetables, the beets, leeks, parsnips, kohlrabi and Swiss chard have all flourished in the long hours of sunlight we’ve enjoyed since July, and I expect to continue to have a good yield through the winter months.

The BC Weather reports state that late July through to September have been the driest months since weather records were first compiled in the late 1800’s. On review, perhaps there is some truth to ‘Global Warming.’ Next year will be better …?

Article #2 Fraser Valley Orchid Show Report...Janice Jenkins

Fraser Valley Orchid Society’s Annual Show and Sale were held on October 20 and 21, 2012 at the George Preston Recreation Centre. This was their third annual orchid floral arts presentation. The theme this year was: "At Home With Orchids".

The classes were:

Family Buffet - Design suitable for the buffet table

Rhapsody in Blue - Design suitable for the dinner table

Engagement Party - Abstract design suitable for the table

Romantic Dinner - Design of your choice

The published information on the impact of CAW on plant health, growth and yield is available in the following sources:

The purpose for the show theme was to present to the public a number of ways orchids can be used in the home. In addition to having lovely orchid plants to grace their homes, the floral art section was created to encourage the public to use orchid flowers in floral designs.

On Saturday afternoon Radina Jevdevic, who also organized the floral arts section of the show, gave a demonstration on how to design a centerpiece and also a corsage.

The show preview, plant sale and dinner were held on Friday evening for members and exhibitors.

We wish to thank the presiding floral art judge, Marilyn O’Neill, who encouragingly gave many constructive tips to exhibitors on how to improve their designs.

Cindy Tataryn was the winner of Best in Show award for her arrangement in the "Engagement Party" class.

See you at the 2013 Fraser Valley Orchid Society Show.

Article #3 Lithops aka Living Stones...

Lithops aka Living Stones are succulent plants from the ice plant family, Aizoaceae. These are native to the hot, dry areas of southern Africa. Nearly a thousand individual populations are documented, each covering just a small area of dry grassland, veld, or bare rocky ground. Different Lithops species are preferentially found in particular environments, usually restricted to a particular type of rock. Lithops have not naturalized outside this region.

Individual lithops plants consist of one or more pairs of bulbous, almost fused leaves opposite to each other. The slit between the leaves contains the meristem and produces flowers and new leaves. During winter a new leaf pair grows inside the existing fused leaf pair. In spring the old leaf pair parts to reveal the new leaves, then the old leaves will dry up. Lithops leaves may shrink and disappear below ground level during drought. In habitat they almost never have more than one leaf pair per head as the environment is just too arid to support this.

In their third year of growth, yellow or white flowers emerge from the fissure between the leaves after the new leaf pair has fully matured. This is usually in autumn but in some varieties such as L. pseudotruncatella can be before the summer equinox and in L. optica after the winter equinox. Two different plants are required for pollination and seeds take approximately 9 months to mature. Seeds are easy to germinate but the seedlings are small and vulnerable for the first few years.

Lithops are one of the greatest of the camouflage plants as the leaves are not green but are various shades of cream, grey and brown, patterned with darker windowed areas, dots and red lines. This helps to disguise the plant in their surroundings keeping it safe from animals and insects looking for a food or water source.

Lithops require pollination from a separate plant. Lithops fruit is a dry capsule that opens when it becomes wet; some seeds may be ejected by falling raindrops and the capsule recloses when it dries out.

Rainfall in habitats ranges from approximately 700mm per year to nearly zero. Temperatures are usually hot in summer and cool to cold in winter, but one species is found right at the coast with very moderate temperatures year round.

In recent years Lithops have become popular as houseplants and many specialize succulent growers maintain collections. Seeds are widely available in stores and over the web. They are easy to grow if given sufficient sun and a suitable well drained soil.

Normal treatment in temperate climates is to keep them completely dry during winter, watering only when the old leaves have dried up. Watering should continue through autumn when the flowers emerge and then stopped for winter.

Treatment for hotter climates includes summer dormancy when they should be kept mostly dry and given some water in winter. In tropical climates, Lithops can be grown primarily in winter with a long, summer dormancy. In all conditions, Lithops will be most active and need most water during autumn and each species will flower at approximately the same time.

Lithops thrive best in a coarse, well-drained substrate. Any soil that retains too much water will cause the plants to burst their skins as they over-expand. Plants grown in strong light will develop hard strongly coloured skins which are resistant to damage and rot, although persistent overwatering will still be fatal. Excessive heat will kill potted plants as they cannot cool themselves by transpiration.History:

The first scientific description of a Lithops was made by William John Burchell, explorer of South Africa, botanist and artist, although he called it Mesembryanthemum turbiniforme. In 1811 he accidentally found a specimen when he picked up a curiously shaped pebble.

In the 1950s, Desmond and Naureen Cole began to study Lithops. They eventually visited nearly all habitat populations and collected samples from approximately 400, identifying them with the Cole numbers which have been used ever since and distributing Cole numbered seed around the world. They studied and revised the genus, in 1988 publishing a definitive book (Lithops: Flowering Stones) describing the species, subspecies, and varieties which have been accepted ever since.

New species continue to be discovered steadily in remote regions of Namibia and South Africa, most recently L. coleo-rum in 1994, L. hermetica in 2000, and L. amicorum in 2006.

|

| Lithops optica var Rubra |

|

| Lithops terricolor ex. Photo: Kara Nursery |

Even if you're an avid gardener there is a very good chance you've never used or even heard of Catalyst Altered Water (CAW), even though its been used to support plant health, growth and yield since about 1975.

What is it?

Catalyst Altered Water is a non-carbonated mineral water containing small amounts of sodium meta silicate, calcium chloride, magnesium sulfate, sulfated castor oil and powdered lignite. It has a pH of 12.34 and is approximately 99.99% organic. The addition of a trace amount (approximately .001%) of sodium meta silicate has prevented full organic certification in the US where CAW was invented and it formulated. CAW attracted public interest in 1980 when the CBS program '60 Minutes' broadcast interviews with people using it in a variety of applications (e.g., drinking; spraying on burns; agriculture, etc; see http://vimeo.com/6596672) . Two agricultural applications in that broadcast (squash and wheat crops) suggested CAW could improve plant growth and yield even in stressful growing conditions (e.g., drought).

How does CAW work?

Dr. John Willard, PhD, inventor of Catalyst Altered Water, claimed his product contains a colloidal particle called a micelle. He suggested the micelle’s strong negative charge attracts water molecules and rearranges their structure. Dr. Willard claimed this rearranged structure makes ‘ordinary’ water (tap water; well water; purified water) more reactive and thus more effective as a water and nutrient transport medium in plants.

How and when to use CAW

You’ve heard the expression ‘just add water’. That pretty much sums up how to use CAW. Just add 60ml (approximately 2 ounces) of CAW to your watering can or reservoir if you are lucky enough to have a greenhouse or a hydroponic garden. You can safely mix CAW with purified water, tap water, well water, distilled water, etc. It is fairly well known in the nutrition industry as a drinking water additive so don’t worry about hurting your favourite plants. It is non-toxic.

You can use CAW any time you water your plants and at any stage in plant growth. You can also use it to support seed germination as it attracts moisture. CAW is an alkaline water (pH = 12.34) that has been shown to raise the pH of any water it is mixed with by up to 2 points. That enhanced alkalinity has potential benefits as a foliar spray. Just add 60mL of CAW to one gallon of any type of water and apply that mixture as part of your normal seed germination or foliar spray routine.

How does it affect plant health, growth and yield?

Catalyst Altered Water is certainly not a magical elixir and research clearly shows that it does not always enhance plant health, growth or yield in every application. The fact this product has been around since the mid seventies however suggests it has some popularity and benefits, as people suggested in the '60 Minutes' program.

Perhaps the most interesting experiments on CAW have been conducted in commercial greenhouses in Canada and the US where both test and control groups of plants have been used. That testing has involved over 100,000 plants including clematis, impatiens, micro and potted spathiphyllum, hydrangea, weigela florida and spiraea japonica. These tests found the following benefits:

Larger and/or greener plants

More blooms or plants blooming earlier

Sturdier stocks or more extensive root systems

Greater resilience in stressful growing environments (eg., drought). More yield per plant, larger fruit/flowers and enhanced flavour and aroma

The published information of the impact of CAW on plant health, growth and yeild is available in the following sources:

Acqua Vitae, Roy Jacobsen, 1992

Catalyst Altered Water, Beth Ley, 1990

"Dr Willard’s Catalyst Altered Water", article by C G Crapper, Maximum Yield, May/June 1999

Editor’s Note: Text in green was revised by the author, October 24, 2012, based on manufacturer’s info re actual organic content.

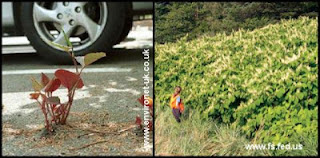

Article #5 Invasive Plant Species - Giant Hogweed

Giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum), also known as "Giant Cow Parsnip," is a perennial and currently distributed in the Lower Mainland, Fraser Valley, Gulf Islands, and central to southern Vancouver Island.

Giant hogweed has numerous small white flowers clusters in an umbrella-shaped head, with stout, hollow green stems covered in purple spots. Dark green leaves are coarsely toothed in 3 large segments with stiff underside hairs, and lower leaves can exceed 2.5 metres in length. Giant hogweed can grow up to 5 metres in height at maturity.

Giant hogweed is a highly competitive plant due to vigorous early-season growth, tolerance of full shade and seasonal flooding, as well as its ability to coexist with other aggressive invasive plant species. Each plant can produce up to 100,000 winged seeds (typically 50,000) that remain viable in the soil for up to 15 years. Plants generally die after flowering.

Warning: Giant hogweed stem hairs and leaves contain a clear, highly toxic sap that, when in contact with the skin, can cause burns, blisters and scarring. WorkSafe BC has issued a Toxic Plant Warning for Giant hogweed that requires work-ers to wear heavy, water-resistant gloves and water-resistant coveralls that completely covers skin while handling the plants. Eye protection is also recommended.

The Invasive Species Council of British Columbia is a registered charity working collaboratively to build cooperation and coordination of invasive species management in BC. Workshops, activities, and events educate the public and professionals about invasive species and their potential risks.

The ISCBC has grown rapidly since its inception in 2004, and is recognized across the country for its leadership in building collaboration on the challenging and growing problem of invasive species.

To report an invasive plant, or for more information, contact the Invasive Species Council of BC (ISCBC) at www.bcinvasives.ca.

|

| Giant Hogweed |

|

| Giant Hogweed |

Article #6 Which is the Best Mulch for You? …by Phil Nauta

There are many mulch types available for your organic garden, but which is the best mulch for you? This article explores some of the most popular types of mulch and ultimately comes to a conclusion with what you should use. What is mulch? It's really anything that we put on the soil surface to cover the ground.

Landscaping Fabric - Not the Best Mulch

Landscaping fabric is considered part of our mulch because it is often placed on the soil under various types of mulch in order to help control weeds. The cheap stuff doesn’t work very well, but thicker fabric can work for awhile before weeds start to find their way through the cracks or just start on top of the mulch.

Unfortunately, that thick landscaping fabric can also stop water from getting down to the soil, especially on a slope where the water just slides down the fabric to the bottom. It doesn’t take long for the landscape to show signs of suffering in this case.

But the biggest problem with this fabric is that it doesn’t allow organic matter to recycle into the soil. When you put landscaping fabric on, it means your soil doesn’t get to eat anymore. This is definitely not the best mulch for organic gardening purposes. Soil needs to be consistently replenished with organic matter, so any of the mulch types we choose have to be composed of organic matter.

Soil is replenished in nature and in our gardens when leaves fall in autumn, and since many of our gardens are low in organic matter anyway, it also happens when we intentionally bring in more leaves, straw, compost and other organic matter to improve the soil.

Putting landscaping fabric in the garden stops all of this and slowly kills the fertility and structure of the soil, and everything living in it. The only potential use is on pathways, since we are compacting them anyway and not trying to increase the organic matter. But we need to look elsewhere for the best mulch.

Why Organic Matter is One of the Better Types of Mulch

When it comes to choosing a good mulch, we need to think, what is mulch for?

Weeds

A continuous thick, dense layer of 2" to 4" of one of the best mulch types is one of my favourite ways to control weeds because not only does it smother most of them out, it makes the ones that do find their way through so much easier to pull, especially if you have been clever enough to regularly hit the garden (and the mulch) with some water.

Weed seeds will always be floating in, but a thick mulch will stop them.

We have other organic gardening chores to do, so eliminating most of the weeds is a good goal. It may be necessary to kill some taprooted or perennial weeds before placing the mulch on top of them. In addition, maintaining a dense, multi-layer plant cover on your soil consisting of a groundcover below and flowers, shrubs and trees above will stop most weeds from growing.

But the reason organic matter is the best mulch is that it pro-vides a huge number of benefits to your garden. In fact, it is one of the most important things you can do. If you use an appropriate kind of mulch (we'll get to what is "appropriate" soon), here are the other main benefits:

Soil Health

The best mulch types are persistently and continuously working to improve the health of the soil. They are being broken down by microbes and increasing the organic matter content of the soil.

Organic matter is an incredibly important part of the soil. It improves soil structure, and as it is broken down, its nutrients are releasing into the soil, making it one of the only types of mulch that improves fertility. It prevents compaction from us walking in the garden and erosion from the wind or gravity on steep slopes. It also moderates the soil temperature, which is good for anything (plant, animal and microbe) living there.

Water

Organic matter is the best mulch because it is broken down into humus, which has an incredible ability to hold onto lots of water. But even before it is broken down, mulch holds a lot of water on its own and allows it to more slowly infiltrate into the soil.

It also reduces compaction (and leaching of nutrients) caused by a heavy rain, and erosion that happens when a lot of rain falls and there is runoff. Conversely, when the sun is shining, it also prevents evaporation from the soil surface.

So the best mulch actually improves the biodiversity of your entire soil ecosystem by giving all manner of critters a place to live, food to eat and water to drink. It even looks good in the organic garden if one of the right types of mulch is used.

So what is the best mulch? Well, it has to satisfy all of the conditions in the above article, so we can probably figure it out by a process of elimination. Let's start with mulches that satisfy very few of our conditions and get rid of them right away:

1. Stones or gravel provide some of the benefits in that they protect the soil from erosion and decrease evaporation, but they do not breakdown and so do not do much to improve soil health. They are not one of the best mulch types.

2. Bark mulch and wood chips are no good even though they are some of the most commonly used mulching materials in the garden. You may have seen them in bags or in bulk at the garden center, or you may have used them in your organic gardening before. They do most of the above things well, but unfortunately, they have a couple of big problems making it one of the types of mulch I never use. Bark mulch and wood chips are not the best mulch types. The first is that they are very high in carbon and very low in nitrogen. This means that the beneficial microbes can pull all of the available nitrogen from the surrounding area, which often ends up causing a nitrogen deficiency in your plants.

And bark in particular is very low in nutrients (so it doesn't improve soil fertility) and often high in toxins (it’s a tree’s first line of defence against pests), so it causes toxicity problems in the soil. It even contains oils that repel water, rather than more appropriate mulch materials that will hold onto water.

3. Straw and Hay are not the most aesthetically pleasing, but they are fairly good types of mulch. They are used in organic gardening, but the main issue for most people will be that it is not always easy to find and it breaks down so quickly that it has to be applied multiple times a year.

You may not want to use straw or hay from ryegrass as it has toxins in it, and definitely not from grass that has been sprayed with pesticides such as Roundup, which is common in many countries. The difference between straw and hay is that hay has seeds, so it will often actually produce weeds.

4. Grass clippings are not the best mulch to use in organic gardening because they get so tightly packed together that they inhibit air circulation. Besides, they are far too important for the soil of your lawn to bring into the garden. They do not contribute to thatch or any other lawn problems, but they pro-vide many benefits so they must be left there.

5. We're getting closer to my favourite of all mulch types, but not yet. With all this talk about organic matter, why not just use compost? A little bit of thought tells us why. It does a lot of things right, but fails to stop the weeds! The same goes with manure, and manure needs to be composted before applied to soil anyway. We should use compost and manure, but they are not really the best mulch. I cover compost in detail in the Smiling Gardener Academy along with cover crops because they are both excellent ways to increase the organic matter content of the soil, but here, we're looking for the best mulch.

The Best Mulch Types

What is mulch, I mean the best mulch - what is it? It's organic matter and it's provided by nature. In a well-designed organic garden, this is one of the only types of mulch that magically appears in our beds in autumn, protecting the soil over winter, and breaking down throughout the following spring and summer until a new batch magically appears in autumn.

Number 1

Of all the mulch types, by far the best for organic gardening is: leaves! They do absolutely everything right. That's why when we're designing our gardens we want to make sure to use plants that make a lot of leaves - not just evergreens - and we want to design the beds to catch all of these leaves.

Leaves are by far the best mulch type

Those that fall on the lawn and non-garden surfaces can be raked into the gardens or mulched right on the lawn.

If you don't have enough leaves, your neighbours will usually be happy to give you theirs, since they would otherwise have to rake them up and dispose of them. In many cities, you can rake your leaves to the curb and a big truck will come by to pick them up. But why would you want to give the best mulch ever away unless you have too many?

Ironically, some organic gardeners do this and then buy the leaves back as leaf mould in the spring. Leaf mould is just leaves that have been slightly decomposed. Leaf mould is one of the best mulch types, too, but in most cases, the gardener would have done much better to save the money and keep the leaves in the garden over winter where they can protect the soil.

If you have a thick enough layer of leaves in your garden (2" to 4" is nice), many weeds will be smothered. You will still get some weeds, but they will be so easy to pull that it won't matter. You can just drop them back on top of the leaves to become part of the best mulch ever.

Some people think leaves are not one of the most attractive types of mulch for the garden, but is a forest floor unattractive? Or is the forest floor covered in 2 inches of bark? We’ve been conditioned to think that bark mulch or bare soil is the most aesthetically pleasing, but if you covered your organic garden in a rainbow of autumn leaves, I think you’ll see it differently, especially now that you know all the benefits they provide. When we remove the leaves, we are breaking nature's cycle and creating more work for ourselves.

So leaves are the number one best mulch.

Number 2

There is one other organic gardening material that doesn't take the place of leaves as the ultimate of all the types of mulch, but it is beneficial to have as well. It's called a living mulch, i.e. plants. A living mulch is a dense plant cover on the soil, especially low growing "cover" crops.

These can be annual crops (also known as green manures) that we plant in our vegetable gardens to protect the soil during certain times of year and to provide organic matter to the soil, or perennial plants (also known as groundcovers) that live permanently in our ornamental gardens underneath our flowers, shrubs and trees.

A good goal is to make sure all of your soil is consistently covered with plants, and cover crops help achieve this goal. Plants send out hormones in the vicinity of their roots that tell weed seeds not to grow.

As long as your organic garden is dense with plants and leaves (the best mulch ever), and your lawn is dense with healthy grass, those weed seeds will mostly stay dormant and you have a whole list of other benefits to which you can look forward.

Mulching All Your Leaves - There Are Exceptions

It is possible to have too many leaves if you have a lot of big trees or if your beds are already covered in groundcovers and you don't want to totally smother them. In that case, you may just have to compost them or give some away, to a friend or to the city, although I have mulched 12 inches of leaves into some lawns with great success.

Actually, when I was a kid, I recall my dad would pile a bunch of leaves in the back of the pickup truck (we lived in the country), head down the street to where there were no houses, drop the tailgate, and hit the gas. It was so much fun watching the leaves get caught by the wind and cover the sky like a thousand red and yellow butterflies. In hindsight, I have no idea why we did this, but it was fun at the time.

I know someone reading this is wondering about oak leaves. I've never had a problem with the fact that oak leaves don't break down quickly. I've always enjoyed that about them because it just means my mulch stays around longer. And nope, they don't acidify the soil. But again, if you have too many, don't force it.

Editor’s Note: Phil Nauta is an organic gardener on the East Coast. His website is extremely informative. Should you wish to avail yourself of this incredible resource, here is the link.

http://www.smilinggardener.com

Article #7 Mealybugs...Various Sites

Mealybugs are soft bodied insects in the family Pseudococcidae, They have a white powdery substance over their bodies and white, waxy filaments projecting from the rear of their bodies. They are unarmored but have a rubbery outer coating that cannot be detached. They are considered pests as they feed on plant juices of greenhouse plants, house plants and subtropical trees and also acts as a vector for several plant diseases.

Mealybugs sexes have distinct morphological differences. Females are nymphal, exhibit reduced morphology, and are wingless, though unlike many female scale insects, they often retain legs and can move. The females do not change completely and are likely to exhibit nymphal characteristics. Males are winged and do change completely during their lives. Since mealybugs are hemimetabolous insects, they do not undergo complete metamorphosis in the true sense of the word, i.e. there are no clear larval, pupal and adult stages, and the wings do not develop internally. However, male mealybugs do exhibit a radical change during their life cycle, changing from wingless, ovoid nymphs to "wasp-like" flying adults.

Mealybug females feed on plant sap, normally in roots or other crevices. They attach themselves to the plant and secrete a powdery wax layer used for protec-tion while they suck the plant juices. The males on the other hand, are short-lived as they do not feed at all as adults and only live to fertilize the females.